Izumi Kato and En Isomoto, President of CHISO Co., Ltd.

Editing and realization Akiko Ichikawa

First Impressions

En Isomoto We first met around the time our company began exhibiting contemporary artworks in the gallery on the second floor of the Chiso flagship store. Shun Takaiwa, who organized this exhibition, and I were having conversations about what exactly defines contemporary art when he introduced us.

Izumi Kato It was about five years ago, I think.

Isomoto That was right in the middle of the pandemic, and the kimono industry was facing a lot of uncertainty. Kimono are something that people wear at gatherings, but due to the pandemic everything from weddings and other ceremonies to traditional cultural lessons where people wear kimono completely vanished.

Kato I’m not very familiar with kimono, but I rarely see anyone around town who’s wearing one. Hearing about what was happening in the industry at the time made me realize how bad things were.

Isomoto There was a bigger issue regarding the craftspeople who work in the industry. It was already an aging workforce, and a lot of people decided to shutter their businesses because the pandemic severely reduced demand for their work. This wasn’t the only thing we were talking about, of course, but for that first year or two we’d go out for drinks and talk candidly about the current state of the kimono industry, and gradually there was this sense that we should create something together.

Kato At the time I was working on an ukiyo-e project and painting on Imari ceramics, so I was just starting to get involved with Japanese artisans in various genres of craft. That made it possible for me to envision us working together.

Isomoto Our company was also at a point where we felt like we needed to take action, so there was a willingness on our end to try something new. We didn’t have the company’s 470th anniversary in mind when we started this collaboration, however.

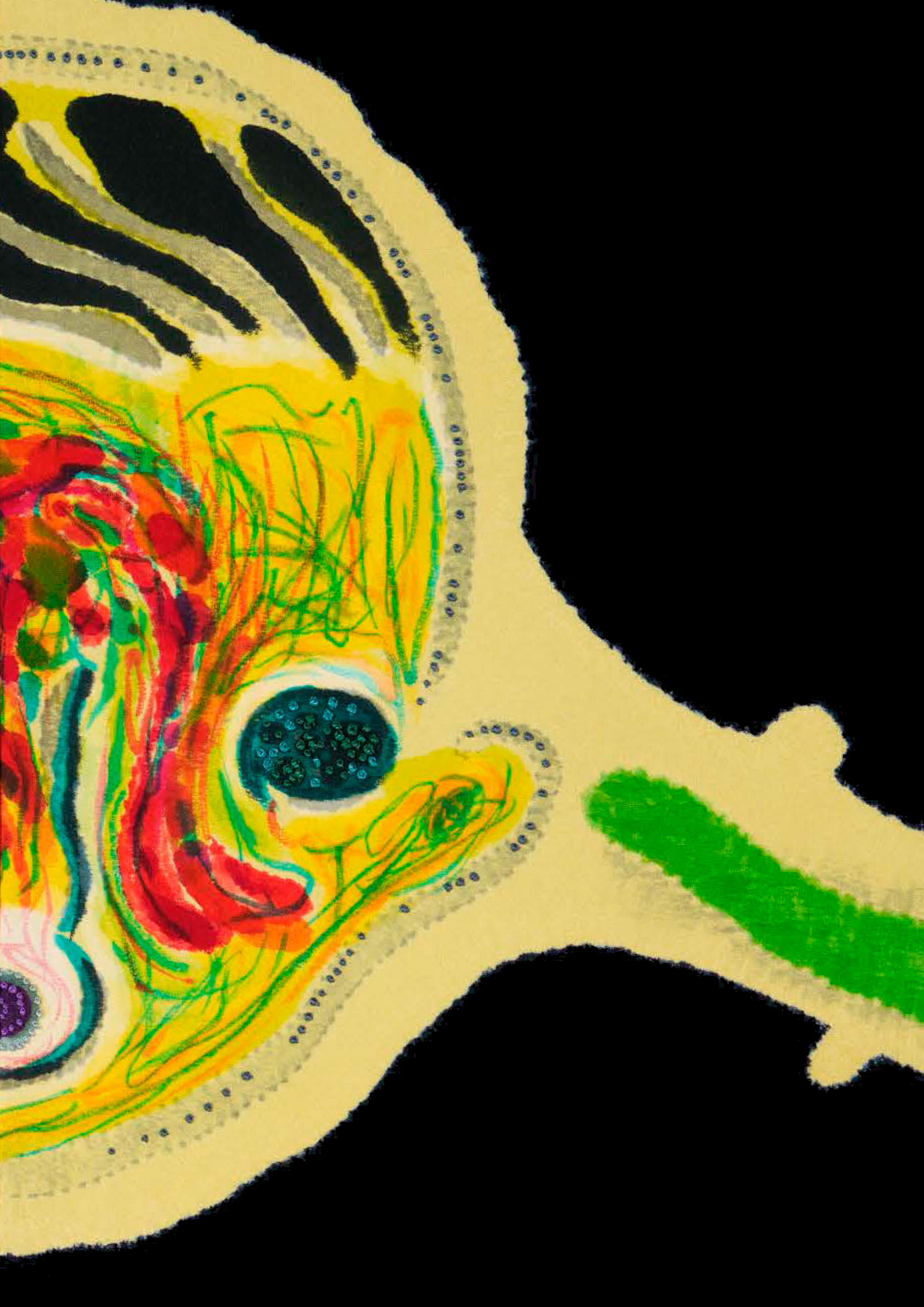

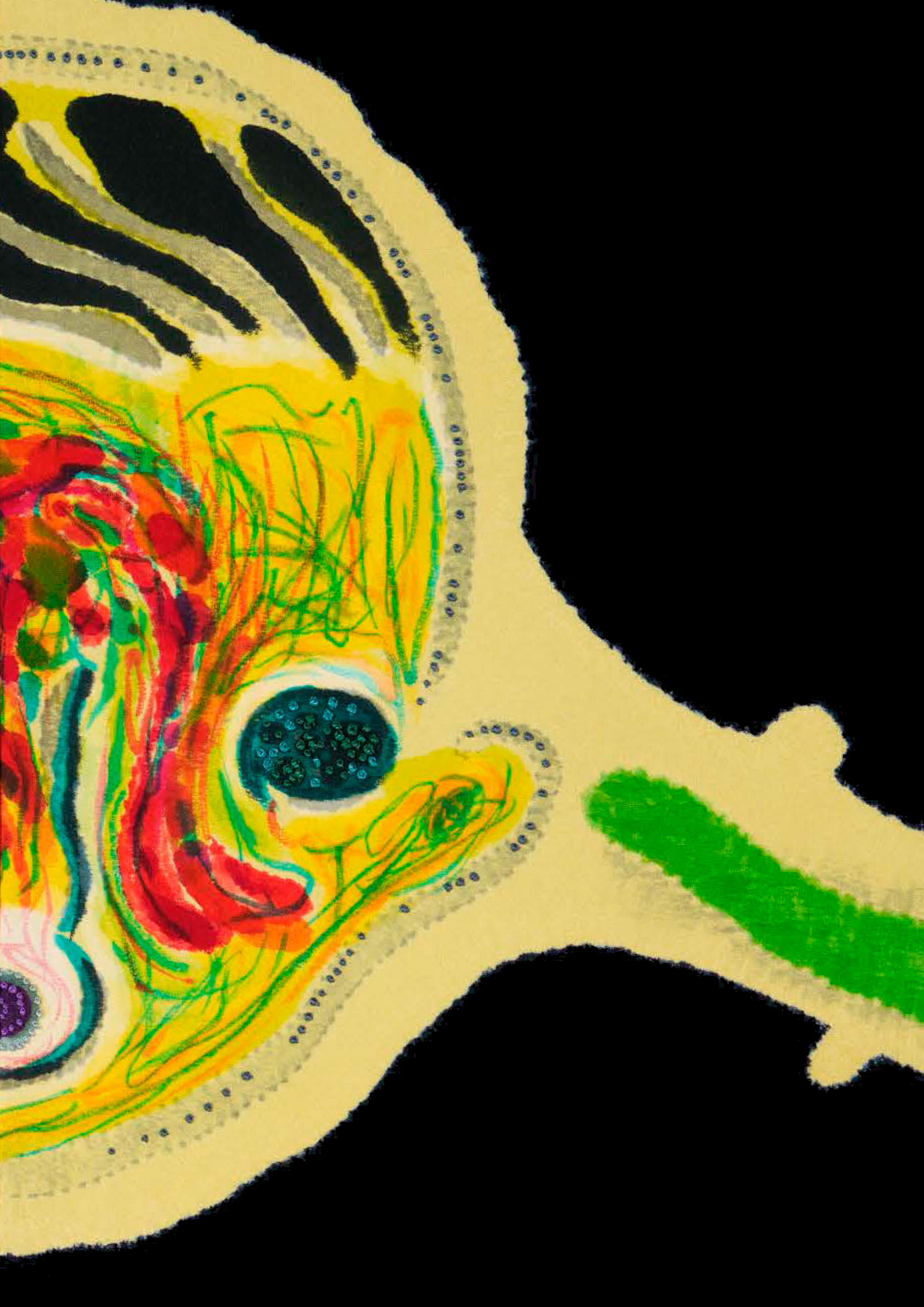

Kato I’m not a designer, and I always just paint whatever I want, so I’m not very good at making something for others. I asked you numerous times if you were really sure that I was the right person for this project. I knew from the start that I didn’t want to just transfer an existing painting of mine onto a kimono, so my first step was to create kimono-specific paintings. The Chiso team sent me some blank sheets of paper with guidelines for kimono design which allowed me to start drafting my ideas.

Isomoto The kimono templates, right?

Kato Right, the kimono templates. They told me to make my drawings with two ideas, Fern Shoot and Horned Owl, and we moved forward from there.

Shared Aspects between Painting and Kimono

Isomoto My first impression when I saw your drawings was that you really seemed to take the traditional kimono into consideration in your compositions. Kimono are a part of traditional Japanese culture, so they operate under an existing framework or set of rules, like coordinating them with the seasons or wearing them in specific places. A lot of what we talked about over drinks for those first two years was how to be aware of that framework, or how to play with that framework.

Kato Paintings are also a traditional form of creative expression that humans have been practicing for thousands of years. To be honest, it’s a medium that’s been wrung dry. Still, there are a number of reasons that I can’t quite put into words why, even in the world I’m living in today, I continue to paint. I think the kimono industry is facing a similar issue.

Isomoto You explained the situation surrounding kimono and painting in a way that was easy to understand.

Kato I think most industries are probably similar, but the question for painters is always why paint when there are so many other expressive media? After all, we’re still working on these unnaturally square objects [that stand in contrast to the natural world]. With kimono as well, Western clothing is readily available in today’s society, but there still exist these origami-like garments that someone invented. Given this, when the Chiso team told me that I could make a kimono, I knew that it wouldn’t be right to break or cut into the form of the kimono itself because that would be like me just showing off by painting on a really bizarrely shaped canvas. For that reason, I made sure from the very beginning not to do anything that would disrupt the actual form of the kimono.

The Process of Production

Isomoto There are between twenty and thirty different processes that are required to complete a single kimono, which means it will pass through the hands of around thirty craftspeople at the Chiso flagship store and at workshops scattered throughout Kyoto City. We have a fair amount of experience working with outside collaborators, but what made this collaboration special was that we were able to have Kato-san use our brushes and personally participate in the Yuzen dyeing process. Looking back over our history, it’s extremely rare for anyone other than a craftsperson to touch the fabric.

Kato It’s a world that most people aren’t allowed into, so I was like, are you really sure this is okay?

Isomoto I could tell that our team was really enjoying the process.

Kato Letting outsiders come into where you’re working can be really disruptive. I know because I’m the same way. Everyone has their own routine, so I was really nervous when I first arrived at the workshop. Everyone was so nice though, and made it so easy to work.

Isomoto You say you were nervous, but I was actually surprised by how naturally you came into the workshop and started painting onto the fabric without any sketches. I was extremely grateful for the way that you talked with the craftspeople and worked alongside them rather than coming in and being overly controlling.

Kato The truth is I would have rather had them do all the work! But if I’d done that, my Hito-gata (human-shaped) motifs wouldn’t have turned out the way I wanted. However, one of the craftspeople at the workshop was more skilled at the realistic horned owl painting, so I left that part to him. There was a definite sense of tension when I was painting because I knew I had only one chance to get it right, but seeing the craftspeople around me so focused on their work made me feel more excited than nervous—it felt like I was taking on a new challenge.

Isomoto I think this collaborative process was an invaluable opportunity for the craftspeople to recognize the work they do every day and enhance their confidence. It may sound presumptuous, but I realized yet again what a quick learner Kato-san is and how much experience he has. Part of what makes the dyeing process complex is the way colors that initially appear matte or dull when painted will change as the fabric goes through other processes, but you were able to anticipate these changes working with the other craftspeople.

Kato I agree, this was an opportunity for me to also reexamine what my abilities and my limits are. Normally, I only make work that I’m motivated to make, but I think it’s going to take me about ten years before I’m able to properly organize my thoughts and explain why I made these paintings with Chiso. This is the kind of long-term mindset I always work with. It’s hard to explain, but I feel like there’s now another drawer in my chest of tools with my work going forward.

Seeing the Final Results

Isomoto It’s only been about five years, but I can see in your work the changes that have occurred over the process of working together compared to when you first showed me your paintings. This is just my personal opinion, but there’s something a little scary or eerie about your early work.

Kato It’s dark, too.

Isomoto [Since then] it seems like your work has gradually become more colorful and pretty, and taken on this sense of gentleness and elegance. I’m not being biased when I say that I think the work you made for the kimono is your best to date. That’s how refined it looks.

Kato Normally, I don’t have much of a sense of accomplishment when I’m painting. I feel it a little bit more with sculpture. But with a kimono, I felt a real sense of joy at seeing it all gradually start to take shape. I had a huge sense of accomplishment getting together with everyone and seeing what we created. It’s refreshing to see something that’s the result of so many other hands beyond just my own.

Isomoto The foundation of kimono as they exist today can be traced back to the early Meiji period when Chiso collaborated with traditional Japanese painters such as Chikudo Kishi (1826–1897) and Keinen Imao (1845–1924), who were representative of the modern Kyoto painting scene, to create new kimono patterns. Until then, kimono had been worn as a way of expressing the wearer’s social status and attitudes, but from the Meiji period on, they began to express emotional aspects like beauty or charm and became something to wear and enjoy. Nowadays, with the change in our values and lifestyles, even Japanese people hardly ever wear kimono or buy them anymore. By contrast, it’s now people from overseas who not only purchase them and look at them, but actually wear them as well.

Kato The work in this show may look like a kimono, but it’s very different from any ordinary kimono. Each one is entirely unique. It’s art. This desire we have to emphasize the new value we’ve created is what makes it contemporary art, I think.

Isomoto With the way that the kimono’s role has changed in terms of clothing, being able to work with a highly sensitive artist like Kato-san has allowed us to gain a new appreciation for kimono, expanding our perspective while also reexamining its value. Even if we can’t formulate an answer right away, I feel like this project has become a vital clue in our search.

Translated by Art Translators Collective (Keith Spencer, Kanoko Tamura)

Edited from a January 15, 2025 conversation at Chiso, and a talk show interview on March 1.